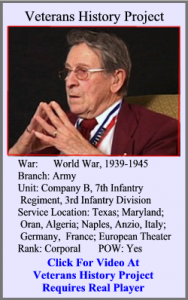

72 years ago, during the Army Ranger assault on Cisterno, Italy, James A Carlascio became a prisoner of war at the age of 18. Prior to his death in 2013, (obituary) , Carlascio sat down for a Veterans History Project Interview (video below) and was also the subject of a Bismarck Tribune article in 2009.

2009 By Karen Herzog – Bismarck Tribune.com…

Video from Veterans History Project – converted to play via Vimeo

When James Carlascio applied to work for the railroad at Jamestown after World War II, his father had to sign for him, because he was only 20.

Carlascio, the son of an Italian immigrant father and a mother who was a “tough Irishman,” he said with a laugh, had returned from the war; it was time to go to work, his dad told him.

Six decades lie between the teenage Army corporal Carlascio was and the 83-year-old veteran he is now. But both the old photos and nattily suited gentleman of today show the same lanky frame, generous head of hair and animated expressiveness.

By the time his dad signed up his still-underage son for his railroad job, James Carlascio already had been drafted; he’d fought in Africa and Italy as an infantryman, one of the “ground pounders” as they were called, with the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division. He’d been wounded and captured. And he’d spent 18 months as a prisoner of war in Germany’s Stalag 2B.

Carlascio and his fellow soldiers were at the 1944 assault on Cisterno in Italy, assigned to capture the town’s out-skirts while the Army Rangers were to take the town itself.

Only, when the Rangers went in, there were machine guns at every door and window, Carlascio said. Of the 767 Rangers who went in, only six returned to the Allied lines.

The infantry was running out of ammunition and medical supplies; their lieutenant surrendered.

Carlascio said that, at 18, he was the youngest POW there, confined in a compound with the rest of his captured unit, along with Frenchmen, Poles and Yugoslavians, soldiers of all nationalities. He remembers all the German shep-herds on chains the guards had.

At the POW camp, Carlascio was put on “horse detail,” feeding and curry combing horses, working in the veterinary and blacksmith shops.

As the end of the war neared, the POWs knew the Allies were getting close – “we could hear them,” he said. Though Hitler had given orders that POWs were to be killed, that never happened. This Carlascio credits to the German people. Instead, the POWs were taken on a forced march, marching basically in a circle for 86 days.

As the end of the war neared, the POWs knew the Allies were getting close – “we could hear them,” he said. Though Hitler had given orders that POWs were to be killed, that never happened. This Carlascio credits to the German people. Instead, the POWs were taken on a forced march, marching basically in a circle for 86 days.

At night, they slept in barns. One morning, they woke up and the guards were gone. They knew this meant the war was over for them.

“Oh, God, we were so happy,” he said.

In 1945, the former prisoners returned home aboard a luxury liner. When they pulled into harbor at New York, Carlascio remembers with emotion how he felt: “We saw that Statue of Liberty. What a beautiful sight.”

Like so many other World War II veterans, Carlascio didn’t talk about his experiences for many years – “I didn’t want to.” But finally, a history teacher persuaded him to talk to students, to answer their questions.

This year, Carlascio received the Chamber of Commerce Citizen of the Year award for 2008 for, among other things, sharing his story with students, for the time he spends at nursing homes, and for his 20-year determination to get a veterans’ Memorial Wall established at Fort Seward in Jamestown.

There, a brick walk honors the names of soldiers all the way back to the Spanish-American War, those killed in action, prisoners of war, and Medal of Honor winners.

In May 2007, Carlascio and his wife, Dorothy, went to Washington, D.C., as part of the WDAY Honor Flight, 189 veterans departing from Fargo to visit the new World War II Memorial in Washington.

The three days they spent there were the trip of a lifetime, a sentimental journey, Carlascio said.

Carlascio was moved by the honor of standing on sacred ground to show respect to “the boys not forgotten.” The memorial is a place every veteran should visit, he said.

“Everyone should go there.”

Carlascio’s sunny expression wavers as he talks about a couple of that multitude who are “not forgotten:” His brother, Tony, wounded in Italy. His brother, Joey, the baby of the family, killed in the Pacific. He was 18.

(Reach reporter Karen Herzog at 250-8267 or karen.herzog@bismarcktribune.com.)

——-

Video Interview at Veterans History Project (uses real player to view)

Comments are closed

Sorry, but you cannot leave a comment for this post.